'

I think that the concept of "Being" is accepted by most people far too uncritically, and requires profound analysis.

When you look at the concept of "Being" closely, it tends to fall apart into a variety of disparate concepts.

In common, everyday language we say, "That is a table"; That is a desert mirage"; That is the definition of a circle"; or, "That's a shame!" We never consider what miracles that simple little "is" performs for our convenience.

Name a visible object which is not made of matter, has no substance or weight, has no specific location in space, and which has a front side but no back. Impossible? A rainbow.

It "is" strange what enormous dissimilarities the little word "is" can obscure. A table, a rainbow, a circle, a mathematical theorem, a desire, an awareness --- all these things seem to exist, yet what do they really have in common? Little, if anything.

One way of dealing with this problem might be to create two different classes of concepts: defined and indicative.

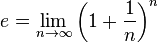

As examples of defined words, we might take "circle", " the square root of minus one", "entropy", etc. Within a particular frame of reference, they have very clear and well-defined meanings.

"Indicative" words are words like "good", "art", "beauty", "God", "mind", and, I would suggest, words like "being" and even "matter".

These words are notoriously difficult to define, and I suggest that their usefulness comes precisely from their lack of clarity, their vagueness, and perhaps even from their logical incoherence.

What I call "indicative" words are like arrows pointing out a direction along which to travel. Their very lack of meaning may make them suitable to be "pointers" in a large variety of frames of reference.

For example, the word "God", even if it is totally meaningless and has no objective referent, has been historically a kind of metaphor or conceptual seed which has suggested concepts of infinity, concepts of causality, etc. which might not have developed without the impetus of this metaphor.

I think we should look more closely at the differences between "defined" and "indicative" concepts, and we should consider the possibility that even meaningless ideas may serve a function in producing meaning. Perhaps the same is also true of meaningless activities.

But we must keep in mind that there are great dangers in confusing the functions of defining and indicating.

There is a story about a student who did not know what the moon is. He went to a teacher and asked, "I've heard people talk about the moon, but I don't know what they mean. What is the moon?"

As an answer, the teacher lifted his hand and pointed to the moon shining in the night-time sky. But the student looked only at the pointing finger and thought that it was the moon! So not only did he mistake the finger for the moon, but he also confused the concepts "dark" and "bright", since he thought that the dark finger was the bright moon!

.

I think that the concept of "Being" is accepted by most people far too uncritically, and requires profound analysis.

When you look at the concept of "Being" closely, it tends to fall apart into a variety of disparate concepts.

In common, everyday language we say, "That is a table"; That is a desert mirage"; That is the definition of a circle"; or, "That's a shame!" We never consider what miracles that simple little "is" performs for our convenience.

Name a visible object which is not made of matter, has no substance or weight, has no specific location in space, and which has a front side but no back. Impossible? A rainbow.

It "is" strange what enormous dissimilarities the little word "is" can obscure. A table, a rainbow, a circle, a mathematical theorem, a desire, an awareness --- all these things seem to exist, yet what do they really have in common? Little, if anything.

One way of dealing with this problem might be to create two different classes of concepts: defined and indicative.

As examples of defined words, we might take "circle", " the square root of minus one", "entropy", etc. Within a particular frame of reference, they have very clear and well-defined meanings.

"Indicative" words are words like "good", "art", "beauty", "God", "mind", and, I would suggest, words like "being" and even "matter".

These words are notoriously difficult to define, and I suggest that their usefulness comes precisely from their lack of clarity, their vagueness, and perhaps even from their logical incoherence.

What I call "indicative" words are like arrows pointing out a direction along which to travel. Their very lack of meaning may make them suitable to be "pointers" in a large variety of frames of reference.

For example, the word "God", even if it is totally meaningless and has no objective referent, has been historically a kind of metaphor or conceptual seed which has suggested concepts of infinity, concepts of causality, etc. which might not have developed without the impetus of this metaphor.

I think we should look more closely at the differences between "defined" and "indicative" concepts, and we should consider the possibility that even meaningless ideas may serve a function in producing meaning. Perhaps the same is also true of meaningless activities.

But we must keep in mind that there are great dangers in confusing the functions of defining and indicating.

There is a story about a student who did not know what the moon is. He went to a teacher and asked, "I've heard people talk about the moon, but I don't know what they mean. What is the moon?"

As an answer, the teacher lifted his hand and pointed to the moon shining in the night-time sky. But the student looked only at the pointing finger and thought that it was the moon! So not only did he mistake the finger for the moon, but he also confused the concepts "dark" and "bright", since he thought that the dark finger was the bright moon!

.